More integrated relationship between post-secondary institutions and industry can boost Canada’s lagging productivity

As Canadian businesses recover from the effects of COVID-19, the productivity and skills gap twins have re-entered the conversation.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada continues to have low productivity scores. Our GDP forecast currently sits below the world average, and that gap is projected to increase over time. Meanwhile, disruptions due to technology, changing market demands and environmental, social and governance initiatives create hiring and retraining challenges for businesses.

The productivity and skills gap dilemma hobbles Canadian companies’ local and global competitiveness and threatens our economic recovery.

Unsurprisingly, these problems are directly connected; productivity is down due to a lack of talent. To fill the gap, we need to rethink our talent strategy.

In Canada, we often view our talent pipeline like a supply chain. Industry advises polytechnic institutions and colleges, and they produce graduates to meet the talent demand. This process is often effective, but a more integrated, partnership approach will take us to the next level.

Industry wants graduates who are job-ready, through a blend of education and workplace experiences. Industry also wants people currently in the workforce to have access to better, faster and more affordable options for reskilling and upskilling throughout their careers. The need for a more integrated relationship is clear.

It starts with a stronger linkage between post-secondary institutions and industry regarding talent pipeline development. At the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT), we have the strategic goal of being industry’s most trusted partner when it comes to addressing their workforce needs.

The word partner is key. We envision NAIT and our industry partners working together in a much more active and cohesive way to create and maintain the talent pool necessary to sustain the economy.

We have established and proven work-integrated learning (WIL) models in post-secondary education, such as apprenticeship, co-ops and practicums. NAIT has approximately 10,000 students, including apprentices, participating in WIL. These models work so well that the Alberta government has recently set an ambitious goal of including WIL in 100 per cent of undergraduate programs.

In addition, the Alberta government wants to expand the apprenticeship model beyond skilled trades. We are re-imagining how the apprenticeship model could enhance education in professions such as IT, business and hospitality.

Under this model, over 50 per cent of a student’s education would be delivered in the workplace. Companies benefit from hiring talent sooner, and students benefit from gaining work experience as they pursue their education.

The other major challenge that is critical for both individual and economic recovery is the upskilling and reskilling of the current workforce. Given the level and speed of disruption across sectors and labour markets, the need for rapid retraining and timely hiring with confidence is crucial.

NAIT is reimagining our value proposition when it comes to lifelong learning. We are evolving and expanding how we provide value to individuals so that we focus on filling the gaps in their skill sets by recognizing the knowledge that they already have obtained through on-the-job training and work experience. We also want to help businesses make good hiring decisions and reduce training costs.

We realized that our value comes not just from our role as a content provider, but also from our acknowledged status as an assessor and validator of skills and knowledge, and our ability to confer a recognizable credential. The concept of a microcredential — a specific credential that confirms a discreet set of skills or knowledge — has been gaining in popularity. Because microcredentials are so focused, they can help people demonstrate the specific competencies that employers are looking for.

NAIT is currently developing a direct microcredential model that assesses a person’s knowledge as a first step in upskilling or reskilling. If the individual passes the assessment, a microcredential is awarded. If not, then short courses can be provided to address only the identified skills gaps. This shortens retraining time and provides valid credentials to ease hiring decisions and talent deployment.

Recovering from the pandemic will depend on a different and integrated approach to address the skills gap and increase productivity. The federal government has a role to play, including supporting workforce reskilling initiatives and enhancing needed technical innovation, but we need ground-level solutions that come from polytechnics and industry working together. A more productive Canada starts with stronger partnerships.

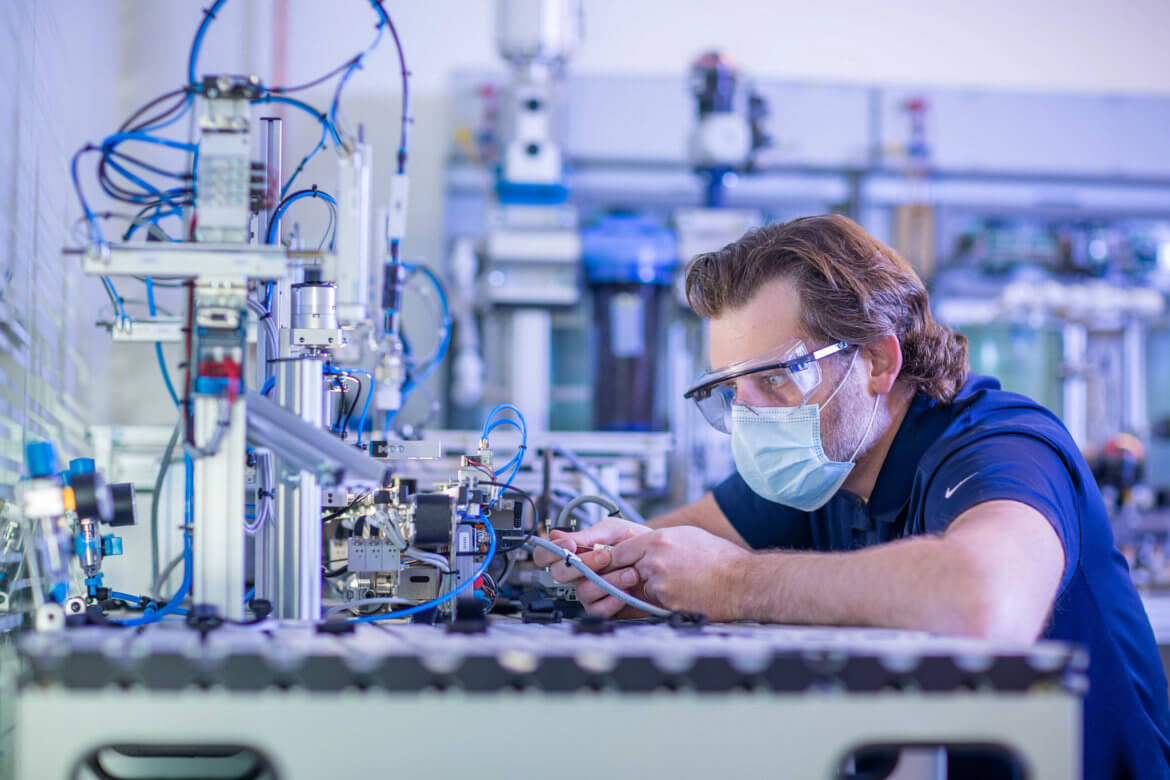

Photo courtesy of the author