But the blind spot is investment in upskilling and reskilling

The future of Canada is not so bright. Data, notably those published in 2023 by the Centre sur la productivité et prospérité (CPP) using OECD statistics, show that the standard of living of Canadians, as measured by GDP per capita, is falling behind some other OECD countries.

In 1981, Canada was in the 6th position out of 20 countries, but in 2021, we are in a dismal 12th place, below the OECD average. If the trend continues, Canada will be in 14th place by 2060.

This situation is due mainly to low productivity growth in Canada. Indeed, GDP per hour worked is among the lowest in OECD countries.

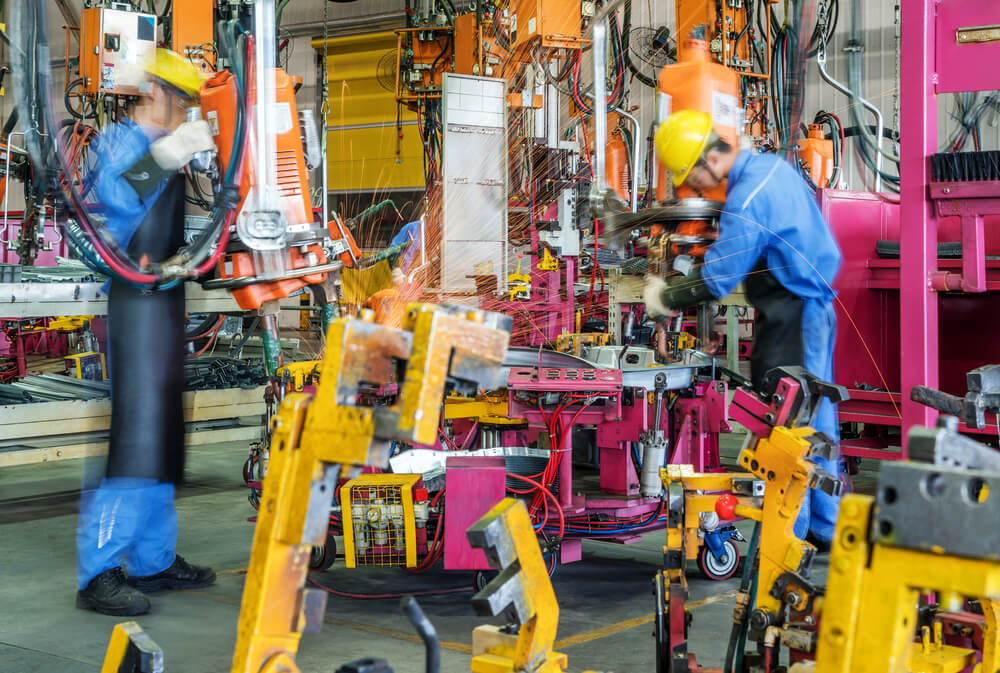

This does not mean that Canadians are lazier than elsewhere. It means that Canadians produce less per hour of work because the tools they use, like computer programs, machinery and robots, are not up to date.

The 2023 CPP report shows that private business investment per employment in Canada is among the lowest in OECD countries.

It’s time the federal government tackled these challenges with innovative policies to stimulate private investment.

Some argue that the solution lies in the intangible sector. Canada needs to address the issue of intellectual property and data as assets.

Canadians are strong innovators because we produce good research in our universities and research centers, but we fail in commercializing these innovations. We are a pipeline of innovation for other countries to exploit. Implementing a Canadian strategy on intangibles would redress the situation according to this viewpoint.

While this approach has merits, it is insufficient on its own to counteract the long-term decline of the Canadian economy.

Low investment in skills development is the hidden side of low business investment in tangible and intangible assets. Even worse, low investment in reskilling and upskilling increases the skills gap. In other words, skills development is the blind spot that must come out of the shadows.

Pundits tend to forget too easily that business investments in machinery, computers robots and artificial intelligence still rely on humans for Canada to reap the benefits. Businesses won’t invest if there are no people with the needed skills to operate and work with up-to-date tools.

Canada has not yet embraced the skills revolution like most OECD countries.

We are a country with a low density and aging population. We have natural resources and an important proportion of our youth have university degrees. However, too many Canadians lack technical and numerical skills. Canada lacks the number of people needed to work and compete in the industries of the 21st century.

Countries ahead of Canada have invested in skills development and they have strategies for updating and reskilling individuals throughout life.

The European Union is working with its members to promote assessment, recognition, development, and investment in essential skills such as digital, literacy, numeracy and green skills. EU countries have also developed active labour market measures to reskill and upskill dislocated workers to a much greater extent than Canada.

Canadians are aware of the skills challenges. A Survey produced by my office and contracted with Nanos in 2019 indicates that millions of Canadians believe that they need training and want to upgrade their skills to adapt and take advantage of future technological changes.

A Canadian economic and social council is needed

To address our skills gap and low business investment, it is urgent that the federal government create an Economic and Social Council which would include federal, provincial and territorial governments along with the private sector.

In 2021, the Prime Minister’s Mandate Letter to the Minister of Finance asked the Minister to establish a permanent Council of Economic Advisors to provide independent policy options on long term and inclusive economic growth to achieve a higher standard of living, better quality of life and a more innovative and skillful economy.

This would be a first step.

Canada also needs to reform Employment Insurance (EI) so that it can be part of the skilled workforce solution. As it stands now, EI collects around $27 billion every year, financed entirely by employers and employees. EI reform is long overdue since the program is not adapted to the 21st century.

These are the kinds of actions we need to take collectively — and urgently — to prevent the doomsday scenario projected by OECD data.

Photo courtesy of DepositPhoto